Complementarity of nature and culture in landscape architecture

An academic paper written during a course "Theory in Landscape Architecture practice", winter 2020-2021.

Abstract

In this paper I explore the nature-culture dualism in landscape architecture practice. With the help of literature study, I argue that the relationship between nature and culture is not mutually exclusive, but rather dialectical, complementary. Neither of them is more significant than the other. I explore how nature-culture dualism may be reflected in practice in the grown and built environment as well as forms, materials, and functions of a place. I have an assumption that the degree of manipulation of the natural environment is correlated with the functions of the place. I create a visual survey as a method to test the assumption. The analysis of the method picks up on the discussion about other common dualities, like sensible and rational, scientific and artistic, aesthetics and utility, objective and subjective, and ethical dilemmas associated with them in landscape architecture.

In this paper I explore the nature-culture dualism in landscape architecture practice. With the help of literature study, I argue that the relationship between nature and culture is not mutually exclusive, but rather dialectical, complementary. Neither of them is more significant than the other. I explore how nature-culture dualism may be reflected in practice in the grown and built environment as well as forms, materials, and functions of a place. I have an assumption that the degree of manipulation of the natural environment is correlated with the functions of the place. I create a visual survey as a method to test the assumption. The analysis of the method picks up on the discussion about other common dualities, like sensible and rational, scientific and artistic, aesthetics and utility, objective and subjective, and ethical dilemmas associated with them in landscape architecture.

Key words: nature, culture, aesthetics, functions, forms, materials, complementarity, dualism, visual

1. The origins of the idea for the article

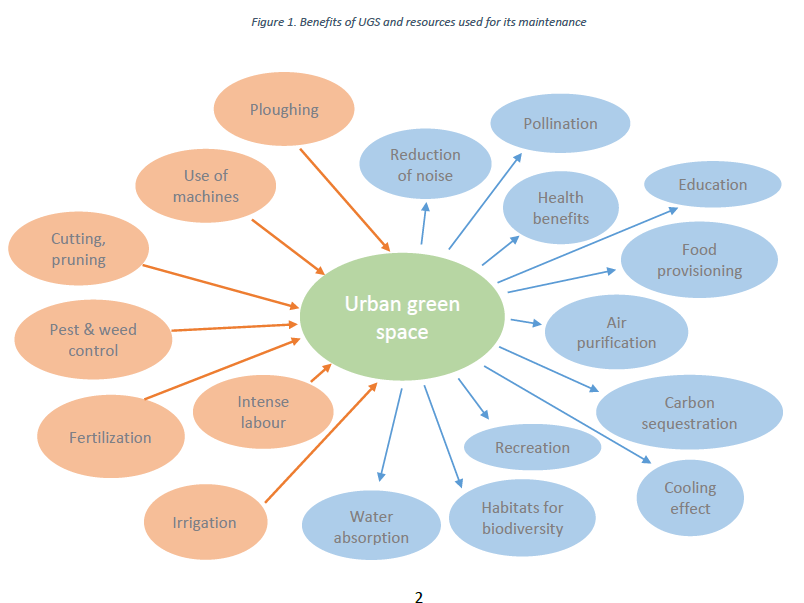

Recently I have done some research about the possibilities and importance of creating no or low-maintenance urban green spaces. My main idea was that the amount of maintenance of a green space should be related to the purpose of the place. Gardens created as pieces of art, need to be maintained to sustain their cultural value, thus the maintenance itself is a part of art. However, places designed to perform functions, like borders, climate mitigation, rainwater absorption, air purification, etc, do not have to require high maintenance. As such places are necessities in urban environment, their maintenance is a necessity as well and the less resources we need to perform maintenance work the higher is the utilitarian and sustainability value. Trollebergsrondellen in Lund designed by Peter Gaunitz is an example of such place (Fig. 1). I believed then that this place is an example of a brilliant solution that is not only sustainable in its essence, providing the city with numerous ecosystem services, requires nearly zero maintenance after the first years of its establishment, but also enriches urban life with a nature-like experience with its dynamic colours and shapes. I was genuinely surprised when I discovered that not everybody had the same opinion about this place as me. While I was nearly advocating for designing most urban green areas along the streets and other urban green spaces the same way, planting meadow-like plant communities there, other people did not actually like the visual qualities of the place. So, I have identified the two important aspects that, I believe have to be present in any good design: aesthetics and functions or utilitarian value.

Figure 1. Trollebergsrondellen in Lund (designed as a meadow

that after a couple of first years requires no maintenance at all)

I have looked at various projects done by contemporary architectural firms. While some projects looked good overall and their descriptions were persuading of the benefits the architects wanted to embed in them, I often thought of some other design concepts that could have more adequate amount of necessary maintenance still fulfilling the functions of the place. I thought of how we could use more natural materials and natural processes in the designs to maximise the utilitarian value. I assumed that the aesthetics of natural elements would automatically create the aesthetic value. However, the case of Trollebergsrondellen has made me to start rethinking my ideas.

I have stumbled upon various publications from an architectural firm called SLA. Their approach is their words is a “nature-based practice in an urban context”, where “nature’s grown environment and the constructed and built environment differ from one another. Although they are not comparable, they are complementary. And to us,”, they say “they together constitute holistic architecture.” (Lippert, 2016). I have studied many of their projects and I have noticed that they often mimic natural forms, however sometimes they use artificial materials to do that. One of the reasons to create natural forms was to bring the nature-like feeling for the citizens into their urban environment. So, I have noticed the following elements that have eventually created the foundation of my idea for the article: forms, materials and functions, where all three can be either natural or artificial (or cultural). In this context I am going to use cultural and artificial as synonyms that describe man-made elements to the contrary of the natural – derived from nature or natural qualities. I have noticed that various designs could use natural forms made of natural materials, artificial forms made of natural materials, natural forms made of artificial materials and artificial forms made of artificial materials. I have made the following diagram to describe my idea:

Figure 2. Natural and artificial forms, materials and functions

Various sources say that form and function are indivisible and are two necessary aspects of being (Steiner, 2006). Processes are reflected in forms and forms affect processes, these two are equal and cannot exist without each other (Steiner, 2006). As functions and forms are proven to be interrelated (even in various disciplines, like anatomy and physiology), I assume that we can not only distinguish natural and cultural forms, but also natural and cultural functions. Natural functions, I assume, are provided by the natural elements, and are associated with the effects of natural environment on people and their activities in a place. For instance, recreational activities, would be the best provided by the combination of natural forms and materials. Cultural functions are supported by the cultural elements in a place and promote social, political, cultural activities, such as political gatherings, meeting with new people, contemplating art (and architecture particularly as a part of the environment). I could not find any research supporting my assumption. So, I have decided to write this paper to collect a theoretical basis that seeks to support the idea, as well as develop a method to test it. Consequently, the objectives of this paper are to:

1. Explore how nature-culture dichotomy is reflected in landscape design practice.

2. Develop and discuss limitations of a method to test an assumption that the degree of manipulation of the natural environment is correlated with the functions of the place. Limitations of the method would lead back to the objective 1. To test the assumption, I have created a visual survey with some additional open questions. Participants were supposed to choose between different visualisations of a place based on their aesthetic preference.

2. Develop and discuss limitations of a method to test an assumption that the degree of manipulation of the natural environment is correlated with the functions of the place. Limitations of the method would lead back to the objective 1. To test the assumption, I have created a visual survey with some additional open questions. Participants were supposed to choose between different visualisations of a place based on their aesthetic preference.

So, this paper raises the following research questions:

1. How is nature-culture dichotomy reflected in landscape design?

2. To what extent can a visual survey shed light on the correlation between the degree of human manipulation of nature and functions of the place?

3. How to address aesthetics and functions (utilitarian value) in landscape design?

2. Methods

I apply literature study as a method, where I analyse academic articles. To test my assumption about a correlation between forms, materials, and functions of a place, I have created a picture-based survey. Landscape visualisations has a potential to receive an emotional response to the proposed solutions from survey participants as well as help with an analytical assessment of necessary changes in the design (Downes, 2014).

I apply literature study as a method, where I analyse academic articles. To test my assumption about a correlation between forms, materials, and functions of a place, I have created a picture-based survey. Landscape visualisations has a potential to receive an emotional response to the proposed solutions from survey participants as well as help with an analytical assessment of necessary changes in the design (Downes, 2014).

In the survey I show 4 different proposals of a place (4 different examples as in Fig 2). First, I planned to create 8 images (4 per place) of two places, one of which represents natural functions and the other – cultural. I chose a yard close to an apartment building for the first one, that has recreation as the main function (natural function). For the cultural function I chose an average main city square in front of a city hall that would represent cultural, historical, social functions. However, because of the time constraints for this study, I decided to limit my investigation to one place – the yard close to an apartment building to prove or disprove my assumption that the domination of natural elements in the area where people live (and spend most of their time usually) is favourable over artificial elements. If the results of the questionnaire prove my assumption wrong, I would either need to revisit the whole concept and find the reasons why it proved wrong (and therefore, having the second case would not help me to prove my assumption, but only either disprove it on the both examples, or if it would prove right in the 2nd case, only confuse me), or if I find methodological reasons (like mistakes in the visualisations), I will need to improve my method first to be able to use it effectively next time with both places.

I chose to create visualisations (Fig 3, 4, 5, 6) in Lumion as it produces images in a style familiar to most people so that my visualisation style will not interfere with people’s perception of the images as representations of places. There was a challenge to make all pictures equally well-designed, where the option that fits the most the assumption is not the most attractive because it is the most well-made. I did not want the visualisations themselves to have any special aesthetic value, so that people would pay attention to the features of the depicted place instead of basing their decisions on the aesthetic value of the images themselves. That is why I chose to use Lumion. How well I managed to succeed, I analyse in the discussion.

Figure 3. Natural forms, natural materials

Figure 4. Artificial forms, natural materials

Figure 5. Natural forms, artificial materials

Figure 6. Artificial forms, artificial materials

My initial idea was to offer participants pay attention to the forms and materials instead of how usable the design is (utilitarian value). So, I decided that every picture should have the same set of user areas: playground, area for adults to sit and have some food (except for the most formal type in Fig. 6), area for elderly, connection to the opposite house, opportunity for urban farming, flower beds, water basin. Every picture has a viewpoint from a window of a house. In Fig 4 I applied theory that natural materials and forms create the most attractive and challenging playing environment and good for building dens for kids of different ages (Kylin, 2003). I tried to focus not only on the forms and materials of objects but also on their placement relative to each other and surrounding objects. The most formal example (Fig 6), for instance, has not only more tendency towards cultural forms and materials in the objects in the space, but also the placement of the objects relevant to each other can be characterised by a more symmetrical arrangement. So, symmetry for instance can be traced on multiple levels (materials, objects themselves and their parts; placement of objects in space). As my assumption is about testing the correlation between forms, materials and functions, I decided to add some open questions to the survey that I called “Design of a yard close to an apartment building” (Table 2). I decided not to mention that I have focus on nature, culture, forms, and materials to see if my assumption proves right for all users, no matter if they are aware of any concepts.

I assumed that because of the peculiarities of how we perceive space versus our perception of visualisations it might be hard to rely only on visualisations to test the assumption about the correlation between forms and place functions in design. I believed that the questions (Table 2) would help and I also decided to have in-depth interviews after people complete the survey. The purpose of the interview was to check whether the results of the survey give me appropriate material to check my assumption and if any changes are necessary to adjust my methodology or the survey itself (formulation and choice of questions, visualisation, etc). I have prepared questions for the interviews (Appendix A), however most often the interviews obtained a free structure and went beyond the planned questions. In the core of my assumption, I had an idea that independent of the previous experience and occupation of the participants, people would prefer natural elements in their yards as natural forms and materials provide the functions of the place in the best way. That is why I did not have any defined focus group. However, I have added a question to the survey about the field of occupation to be able to analyse this aspect as well in case any correlation is noticed.

3. Nature and Culture

Nature and culture are often perceived as two opposite terms, similar to the dualities like, rational and sensible, mind and body, form and function, art and science, Yin and Yang, day and night, sun and the moon, light and darkness, movement and stillness… Often, we can hear discussions whether nature in a city is ever possible as if nature and built environment are two opposites, how can we combine them in one? But is there really a pure nature and a pure culture?

People are not the only species that adapt natural environment to their needs – bees, aunts, birds, snails are just a few examples of how different species use inert materials to construct their physical environment (Steiner, 2006). Similarly, built environment (the product of culture) resembles beehives, aunt hills, nests, and shells in its purpose. Culture is an instrument of adaptation, where design and planning are tools for resilience that is necessary for our health (health according to WHO is the ability to recover from disturbances) (Steiner, 2006).

Nature and culture are often perceived as two opposite terms, similar to the dualities like, rational and sensible, mind and body, form and function, art and science, Yin and Yang, day and night, sun and the moon, light and darkness, movement and stillness… Often, we can hear discussions whether nature in a city is ever possible as if nature and built environment are two opposites, how can we combine them in one? But is there really a pure nature and a pure culture?

People are not the only species that adapt natural environment to their needs – bees, aunts, birds, snails are just a few examples of how different species use inert materials to construct their physical environment (Steiner, 2006). Similarly, built environment (the product of culture) resembles beehives, aunt hills, nests, and shells in its purpose. Culture is an instrument of adaptation, where design and planning are tools for resilience that is necessary for our health (health according to WHO is the ability to recover from disturbances) (Steiner, 2006).

Landscapes respond and change to both natural and cultural factors. We alter our environment both purposefully and unpredictably (Spirn, 1996). Human intervention into the natural environment includes not only physical manipulation, like use, construction, and maintenance, but also has a more subtle aspect – through perception, conceptualisation, memory, mythology (Spirn, 1996), which in turn affects how we experience the environment and whether we are about to transform it and how. This paper focuses mainly on the physical manipulations.

Except for savannahs, wetlands and flood plains, most land that has been inhabited by people strives to naturally transform into a woodland (Reynolds, 2016). The strongest factor that stops them from doing so is maintenance. Mary Reynolds – an Irish landscape designer – says in her book “The garden awakening”: “Most of our gardening energy is spent trying to stop our gardens from becoming what they want to become. We call it ‘maintenance’”. A landscape can be completely altered depending on the way it is managed (Spirn, 1996). It can be constructed and maintained to look even as wilderness. The best examples of such landscapes are the works of Fredrick Law Olmsted, like Niagara Falls and Central Park (Spirn, 1996). In these cases, the consequences of human intervention in natural environment are deliberately concealed by a constructed wilderness. It is done by approaching the place as a system instead of a structure (Spirn, 1996). Though maintenance keeps being opposite to wilderness and even such constructed landscapes as Central Park is by many perceived as untouched (Spirn, 1996).

The built and grown environment are “mutually exclusive and interdependent at the same time” (Andersson, 2014). The built environment is characterised by finished structures made of solely abiotic and synthetic materials, while the grown environment is about ever-changing systems made of living matter (Table 1). Traditional architects tend to approach the grown environment in the same way as the built. Euclid´s treatise “Elements” and Cartesian thinking are the foundation for their approach to the built structure, but it does not usually work to create living organic systems, when we work with the grown environment (Andersson, 2014). Nature and the built environment are “equal parts of the spatial composition” (Andersson, 2014). As I mentioned in the introduction, the architectural firm SLA believes that nature and culture complement each other instead of contradicting each other. Complementarity of the built and grown environment allows the equal presence of both natural and human processes, both structures and systems. To achieve sustainability in our designs there should be a balance between the two, where both grown and built are treated equally important to sustain our life on the planet.

The shift towards an ecocentric view and increase of environmental awareness in 1960s lead to renewal of the debate about ethical and aesthetical aspects of sustainable design (van Hellemondt & Notteboom, 2018). Ian McHarg´s ecological design method implied that sustainable designs would automatically have aesthetic value as they would include and represent the natural beauty. However, it was criticized as many designs looked shapeless and unmanaged (van Hellemondt & Notteboom, 2018).

How a landscape design looks has a direct effect on us and therefore is directly connected to its functions. Olmsted believed that an impressive natural scenery exercises our brains without purpose bringing enjoyment and refreshment (Spirn, 1996). Olmsted himself “found relief in "natural scenery” as opposed to "artificial pleasures" such as theatres...” (Spirn, 1996).

So, how exactly do natural and cultural aspects are reflected in a design? I have studied some architectural projects, and I have noticed that various designs have a variety of combinations of natural and man-made forms and materials. So, I argue in this paper that nature-culture duality is reflected in landscape design in forms, materials, functions and intensity of maintenance.

Natural and man-made (cultural) elements in landscape design

Natural forms are all those that are found in nature and cultural forms are man-made (even when people try to mimic natural forms the sole act of manipulating adds cultural values to the forms and consequently to the place). So, there is a continuum of natural and cultural forms. A square is an example of the ultimate artificial form that does not exist in nature, while irregularly curved shapes are the examples of natural forms. Symmetry is characteristic of cultural (artificial forms) and asymmetry – of the natural. All landscapes and places are situated somewhere on the continuum between pristine nature and human creations and therefore represent a relationship between nature and human activity (Brady, 2006). Principally all landscapes are hybrids of nature and culture. A garden – the most descriptive example of a hybrid place that emphasizes the intrinsic interrelation between its natural and cultural elements, processes. (Brady, 2006). All garden styles are located on a continuum from formal gardens (with straight lines and geometrical shapes) to informal, naturalistic gardens (characterised by curving lines, irregular shapes) (Thompson, 2014). Early in history gardens were mostly formal as it is easier to do surveying and measuring with straight lines and regular geometry, build with regularly shaped bricks, digging straight canals and ditches. One of the best examples of formal gardens is Versailles, where “nature was kept under tight control” (Thompson, 2014). The interest in empiricism lead to the appearance of less formal and more naturalistic gardens carefully designed with irregularities of natural forms (Thompson, 2014). Tendency towards more informal designs was getting stronger with time and nowadays is clearly reflected in the opposition of “manicured lawns and wildflower meadows” (like the previously mentioned Trollebergsrondellen) (Thompson, 2014). Materials can also be classified as natural and cultural (or rather man-made or artificial, synthetic). Natural materials are those taken directly from nature, artificial materials are synthesised, modified by people. Usually, synthetic materials perform certain utilitarian functions, like safety or durability. For instance, a combination of natural and artificial materials is preferable for areas close to kindergartens (Männik & Philipson & Linnros, 2017) Even though natural materials are more attractive for play, they are less durable in the areas and require more maintenance (Männik & Philipson & Linnros, 2017). Artificial materials (plastic, concrete) seem less attractive when they are worn in contrast to the natural materials (like wood, stone) that become even more appealing and often look even more valuable with time (Brady, 2006). Old artificial materials are associated with damage as in their essence their “finished character” intend to resist natural forces (Brady, 2006).

Combination of various materials and forms places objects on the nature-culture continuum (Fig.7). For instance, a hedge clipped into a regular shape (4) and a dune-like concrete surface (2) are located between an unmanaged piece of forest (1) and a flat straight concrete fence (3). A complex interrelation of natural and cultural elements can occur in such objects like a hedge made of green plastic, that has a regular artificial shape, but its leaves all have various natural forms. So, this object would be more “natural” compared to the same hedge but with abstract simplified leaves or of an unnatural plastic colour. The most important factor that affects the placement of an object on a culture-nature continuum is the obviousness of the presence of human intrusion into the natural processes, or as discussed before - maintenance.

Nature and culture are not only abstract concepts that inspire discourses about the relationship between humans and their environment. The grown and built environment are the practical concepts that reflect this duality. Moreover, forms, materials as well as functions of a place, I assume, can also be classified as either natural or cultural (man-made). The combination of a variety of natural and artificial elements in design places it somewhere on the continuum of landscapes as nature-culture hybrids.

Figure 7. Examples of combinations of natural and artificial forms and materials

4. Survey results and method discussion

Most respondents chose option with natural forms and natural materials as their favourite (only one person chose a different option – D (natural forms, artificial materials). Many people mentioned the presence of nature, “a touch of the wild”, irregular shapes as the most beautiful, attractive, corresponding to the recreational functions (Appendix B – survey results). Most respondents submitted their answers, however with some respondents I had only interview after they have accustomed themselves with the survey and thought of their answers. The main ideas from the interview was added to the column corresponding to the last question in the survey (Comments) in the results table (Appendix B).

While the results of the survey itself were promising and could support my assumption, the ideas discussed during the interviews highlighted important issues in the method design and visualisations. First, several respondents mentioned, that questions should be formulated simpler and preferred multiple-choice questions than open answers. While I expected that this survey takes only 5-10 minutes, for some people it took more than half of an hour to complete.

One respondent expressed very interesting insights into his preferred green space and issues that could arise when giving this survey to people with various backgrounds and places of origin. His favourite type of a park is alike English gardens, where there is an imitation of abandonment. Examples of such parks are Vorontsov palace and Sofiivka gardens in Ukraine (Fig. 8, 9), where there are imitations of ruins, rockfall and natural chaos. There are two big botanical gardens in Kyiv – “new” (Fig. 10) and “old” (Fig. 11) as called by the locals. The respondent said that he actually prefers the “old” as it fulfils the functions of a green area better according to his opinion: “Even though it is located in the very centre of the bustling city, you come there, walk down into the valley (that has actually been deliberately created when the park was constructed) filled with tall old trees, that create coolness, fresher air. As it is not particularly maintained, some constructions, like little street borders and stairs, are partially ruined and this gives a feeling of the presence and power of nature that took over. Beauty is not the primary factor... but the state, atmosphere of the place, it affects you, makes you plunge into yourself, calm down, relax, while the city life beyond this park makes you always be focused on things outside of yourself, city provokes you constantly to react to its challenges” (a survey respondent).

The respondent believes that people who were raised not in the capital and come there instead at some later point in their lives, have most often a different attitude towards the city rather than people who grew up there. The non-residents think of it as a place to conquer, the city environment invigorates them, inspires, challenges, while the residents think of it as their place of habitation. Natural elements in the environment are appreciated by the city residents more, while those who grew up in a countryside, associate nature with “digging potatoes”, they go to nature to work (farm), rather than relax. Therefore, a favourable yard close to an apartment building for the residents of the city would most probably include more natural elements than those who came to the city to “conquer” it - the cultural, artificial elements is what they appreciate in the city environment, even close to their homes, most probably. The survey can´t address such complexity and a different approach might be necessary.

Doing visualisations for the survey helped me dive into the topic, explore nature-culture dualism, forms and materials, relationship between aesthetics and design, role of visualisations in design. Furthermore, preparing a survey and creating visualisations of the four different visions of a design of a yard helped me try out my own ideas and see what works and what does not. I believe that the practical part of creating the survey and visualisations helped me immerse myself into the topic better and get additional valuable insights alongside with the literature study.

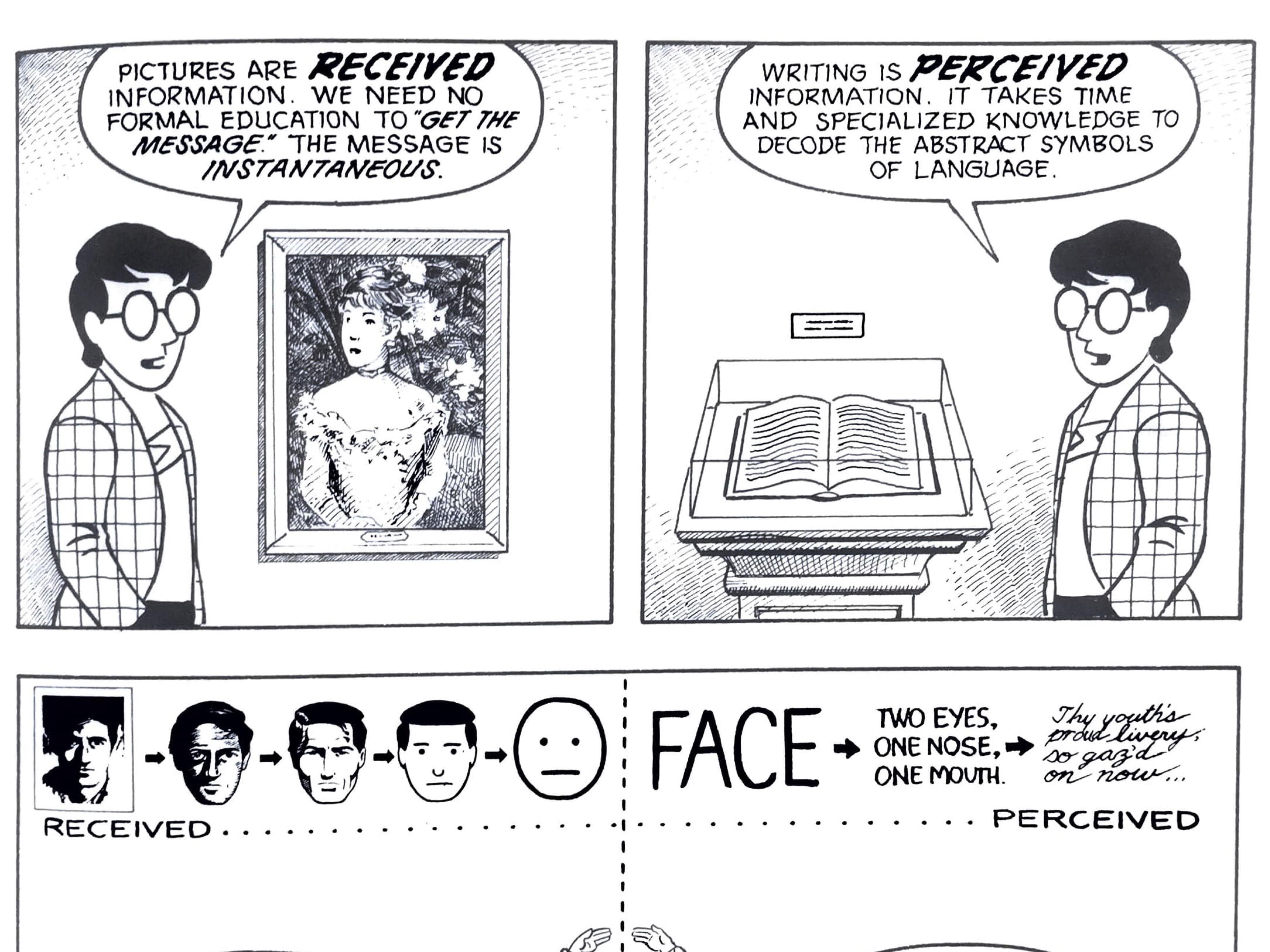

Particularly, I have explored the limitations of the chosen way to create visualisations. Even though Lumion helped to produce images that are exactly the same style, when used on its own (I additionally used SketchUp to build some objects) it is limited in developing attractive visualisation. It is very hard to create a well-balanced composition and both significant and less significant parts of the image look exactly the same, so participants found it hard to understand what to look for in the images. Even the slightest adjustments of contrast, scale, brightness can either enhance or suppress the perception of an object. Even if an object can be recognised, it might be still hard to perceive it (Downes, 2014).

I tried to experiment with tools offered by Lumion and create unusual combinations of forms and materials (like a pool of an irregular shape made of a transparent glass). However, this made it harder for people to understand what it is. One of the respondents has mentioned that it was really hard to understand some objects (like the red object in playground at Fig 6). So my insight from this outcome was that everything in such visualisations should be recognisable from real-life experience, be easily associated with forms, materials, objects that people encounter in their lives on a regular basis, not to confuse and help in answering questions of the survey. I believe that it is important to use additional rendering programs (like Photoshop) to achieve quality of visualisations that convey message in a clear and appealing way. If an image is interesting, a person might give a more elaborated opinion. But that quality was missing in the visualisations I made. One of the respondents also told that when anybody looks at potenatial designs that they could have in their yard, they immediately think of the functions (whether they can easily get to the bus stop nearby, if their kids will be safe there, if they can walk a dog and any other use that they have in their lives). However, I can´t always know what they do in their everyday life, their memories, experiences, associations they might have, so this makes my task nearly impossible. My initial idea was to create visualisations that offer various combinations of natural and man-made elements and I was expecting people to decide on their preference based on the aesthetic value of the imaginative places. My aim was not to create designs from the perspective of use, but I was focused on the aesthetical value of forms and materials. However, places are created through experience (Tuan, 1974) and as Stig L. Andersson says, aesthetics is not about how a place looks, but how it feels (Andersson, 2014). Aesthetics is what makes us wonder, discover, imagine, think (Andersson, 2014) and it is hard to always “create” a place for everybody only through visualisation, as the experience is limited to looking at a 2D image (3D might offer more, but still far from real life experience).

Even though I tried to emphasise that it is important to focus on the general feeling of every image – on the aesthetic aspect – it was hardly possible for people to distinguish between what a place looks like and its functions. That lead to people imagining the place in different weather conditions and seasons and used by a variety of user groups. Therefore, we need to address visualisations with a democratic approach in mind, where we design not only for the users but with them as well (Wistrand & Michaelsson, 2017). Applying norm-creative visualisation, where we visualise a design including a variety of scenarios that could lead to inequality or dissatisfaction with the use of the place (for instance, by visualising it on a rainy evening, where the place could feel unsafe) that help us improve the initial design by addressing the criticism that rise from the discussion of these norm-critical visualisations (Wistrand & Michaelsson, 2017). By addressing and showing how design responds to various complex circumstances eith potential inequalities, helps respondents give the most elaborate answers and therefore help us improve the design.

Landscape is not what actually is, a “landscape is a way of seeing” (Rose, 1992), therefore observation which directly implies the presence of a subject looking at an object is the key to the term “landscape”. We immerse in the landscape, experience the world through movement, where not only our senses are active, but also our memory, conceptualisation as well (Tuan, 1974). However, there is an interesting angle to this discourse presented by John Wylie, when he took his coastal walk and investigated that landscape is not merely the “way of seeing” but, as he says “the entwined materialities and sensibilities with which we act and sense” (Wylie, 2005). It is hardly possible to separate subject and object, at some point subject may cease to exist immersing into the surroundings, as it is continuously affected by the “materialities” and “sensibilities” of the place (Wylie, 2005). “The narrator” (Wylie, 2005) who describes and conceptualises the landscape is an outcome of the experience they have in the landscape, not a preconditioned subject that has completely predictable perception of the environment. This complexity of the interconnection (and again, like with nature-culture duality – complementarity), constant cooperation between subject and object makes it even harder to rely solely on visual survey, where visual perception is prioritised, as a tool to test such complex assumption, that what we see (reflected in forms and materials, as chosen in this paper) has a direct connection of how we use the place, how we feel in it and experience it. And even if we can reach some results, we can never be sure that what people think and feel about a landscape on a proposal visualisation, will think and feel the same way when the same design is implemented. Our perception of a place is different whether we experience it in real life or through visualisation or photography (Downes, 2014).

Even though the visual survey led to multiple critical ideas and does not suit to test the assumption about the correlation between forms and functions in landscape design, it became (as any other way to represent a landscape would be) a material for discussion about complex and important questions important in the practice of landscape architecture. Even though a survey itself can´t be used to give definite answers, I believe it can become a powerful tool to generate a dialogue with various stakeholders and potential users of a future design. A fruitful communication gives deeper understanding of potential weaknesses and its possible solutions to achieve a more sustainable design.

So, while a visual survey is a useful method to spark discussions that contribute to the improvement of a design, it is not enough to prove a correlation between forms and materials with the function of a place, where natural elements are preferred for a place with natural functions, and cultural (artificial) elements – for the one with cultural functions. Perception of environment is a complex process that includes senses, conceptualisation, memory, associations, as well as directly connected to expected functionality of a place. Similarly, to an actual design, even visualisations of an abstract place should address aesthetics and functions equally, to be able to lead to comprehensive results.

5. The role of aesthetics and utility in landscape design

5.1. Perception of aesthetics and utility in nature-culture hybrids

As mentioned previously, most landscapes are hybrids of nature and culture. Therefore, the perception of a place cannot be strictly divided into appreciation of art separated from that of nature (Brady & Phemister, 2012). Instead, these places are associated with a co-dependency between “human creative practice and their experience of nature” (Brady & Phemister, 2012). The elements of the grown and built environment are in a dialectical relationship, that leads to the formation of “the third object” that has its unique aesthetic significance constructed through the interaction of the two opposing forces – nature and culture (humans) (Brady, 2016). The natural processes and “artefactual intentionality” have a harmonious interplay that creates aesthetic qualities of the landscape (Brady, 2016). The dialectical aspect of any landscape therefore “reveals the duality of its origin” (Brady, 2016). Nature and culture are in a dynamic, active relationship, where neither is more important than the other. Each aspect mutually conditions the other therefore they would be best described not as a duality but as a hybrid.

The results of the survey showed that it is hardly possible to perceive a place from purely aesthetical point of view. As Catherin Dee says, “form must be useful form” (Dee, 1958). What is useful varies largely between each individual. However, as function is inseparable from the form, it should always be equally important in the design. The discourse about the dominance of either aesthetics or utility probably has begun since the first landscape intervention on the planet. Humphry Repton, a successor of Brown Capability (was an important figure in landscape design, who made a turn toward more informal, organic designs), believed that “utility must often take the lead of beauty” and “convenience be preferred to picturesque effect in the neighbourhood of man´s habitation”(Thompson, 2014). However, the separation of aesthetics and utility in the creation of survey visualisations, for instance, was, I believe, one of my greatest mistakes. The aesthetic aspect of a landscape is an integral part of it, as much as its utility.

Utility of a design can be measured by how well it meets social, ecological and economical needs. This type of design can be called ecological (van Hellemondt & Notteboom, 2018). There are two views on the aesthetics and ecology. One is that ecological designs are automatically beautiful for users. In this case we often need to consider that environmental awareness and understanding of the environmental, social, economic benefits of a design alters the users’ perception of the places as more beautiful. That is what I have observed is happening with the case of Trollebergsrondellen in Lund, where the low maintenance meadow is more attractive to people who know about the benefits of the design. Our perception of a landscape is self-referential, where our egoistical (including both aesthetic and practical aspects) defines our appreciation of nature (Unterweger & Schrode & Betz, 2017). Therefore, additional knowledge about the benefits of an ecological design presented to the users increases its acceptance (Unterweger & Schrode & Betz, 2017). The second view is that beauty belongs to arts, where natural appearance is in focus while natural functions, processes are left out of the picture (van Hellemondt & Notteboom, 2018).

Explorations into the role of aesthetics in landscape design helps to avoid creating ecological designs based on solely “mimicry of nature” and helps to create hybrid landscapes of natural and man-made elements (van Hellemondt & Notteboom, 2018). These hybrids enriched by the complexity of the opposing characteristics of natural systems and cultural structures allow for the creation of landscapes that “matter spatially, culturally and ecologically” (van Hellemondt & Notteboom, 2018).

As nature and culture, aesthetics and utility are complementary to each other. Neither should be preferred in practice. For the last century architecture relied most on the rational thinking, the scientific aspect of it, leaving aesthetics out of focus (Andersson, 2014). This, Stig L. Andersson believes, lead to the variety of global problems. Aesthetics and rationality are equally important and sustainable decisions are those that balance the two (Andersson, 2014). Purely rational decisions simply have an incomplete basis and therefore cannot lead to long-lasting truly sustainable designs (Andersson, 2014).

Similar to the grown and built environment neither aesthetic nor utilitarian value in design should be silenced in favour of another. Both are equally important and has to be balanced in architectural practice.

5.2. Ethical dilemmas associated with dualisms in landscape architecture profession

Nature vs culture

The implications of the perception of nature and culture as dualism affects landscape architecture as a professional field as well. The duality is even represented at a national level in many countries. For instance, in Sweden, natural and cultural preservation of landscape is divided between the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (responsible for the natural heritage) and National Heritage Board (responsible for the cultural heritage) (Germundsson, 2005). This division promotes lack of collaboration between different expert fields and therefore often misses important insights that exist at the intersection of nature and culture. Issues associated with the division and possible direction for solutions become obvious when we transform our perception of landscapes as nature-culture hybrids.

Landscape architecture not only creates aesthetic experiences, but also is an “active, deliberate…catalyst, that… produces systemic landscape-scale change” (van Hellemondt & Notteboom, 2018). Ian McHarg was calling for us to apply the dual lens of nature and culture to “halt suburban sprawl, to protect prime farmlands and environmentally sensitive areas, to redirect development and investment to existing cities, and to green those cities and reduce the urban heat island in the process. We need to design with nature to heal the earth” (Steiner, 2006). So, landscape architects have a mission to reconnect nature and culture, science and art, aesthetics and utility (van Hellemondt & Notteboom, 2018).

Creativity vs problem-solving in landscape design and landscape planning

Landscape architecture includes two complementary activities - landscape design and landscape planning. They can be distinguished by binary oppositions, like artistic – scientific, small – large scale, creative – problem-solving (Thompson, 2005). The two activities are similar to nature-culture dualism. Alike nature-culture while they represent two poles of a continuum, relationship between them “is more like the yin and yang symbol: there is always a bit of planning in design and a bit of design within planning” (Thompson, 2005).

Landscape architecture has as much art in it as science. Creativity and rationality are the two aspects of the profession that complement each other as much as nature and culture in designs (Thompson, 2005). Capability Brown named himself a “placemaker” and “improver” and Law Olmsted was creating timeless designs that solved problems (Spirn, 1996). No matter how much we could discuss that Olmsted´s designs were destined to be invisible for most of the users and how he has contributed to making landscape architecture “an invisible profession” (Spirn, 1996), his designs served the purpose he had planned for them. Landscape architecture is more than art and more than science – it is the dialectical interplay of the two. We solve complex problems and beauty of the designs can be as much a solution as their utilitarian value.

Aesthetics vs Utility

As I mentioned in the introduction, I became curious about what affects people’s opinions about the look of green spaces, like Trollebergsrondellen (Fig. 1). I assumed and found a proof in literature that awareness of the benefits of a design may increase chances of the place to be perceived as beautiful. However, while it is our mission as landscape architects to design solutions to the contemporary challenges, I think that places we create should also please the eye of the users, no matter if they are aware of the functions and benefits of the design.

Objective vs Subjective

Since I believe it is important to make places that people enjoy no matter how much they know about the design benefits, do we have to be objective in our decisions and always find compromises between our concepts, visions and what people want?

The visual survey chosen as a method in the paper seek for objective answers as I assumed that forms and functions are interrelated, and that majority of people would prefer natural elements for a place with natural functions. I tried to prove that everybody independent of their background prefers the same environment. The limitations and criticism of the originally suggested method to objectively test the assumption led me to the idea that we as landscape architects don’t have to be objective in all our decisions and designs. Our work must be in line with our beliefs and concepts we apply. Some of the participants of the survey has pointed out that what others think might be irrelevant compared to the original view of the landscape architect that is the true direction to follow. Stig L. Andersson says that he always uses “personal perspective as a starting point” (Andersson, 2014). “It is only the personal vision, the personal view of the world that is interesting. The objective is irrelevant” (Andersson, 2014). However, I believe, we must make sure that our work has a response in real life. Therefore, at any stage we should welcome dialogues with other people (colleagues, experts from other professions, potential users, other stakeholders). As Stig L. Andersson says it: “Architecture can not only be in conversation with itself. It must be in dialogue, in constant conversation with the world” (Andersson, 2014).

Conclusion

In this paper, explorations into the relationship between nature and culture in practice – the grown and built environment – lead to an assumption that natural forms would be best suitable for places with natural functions, and cultural forms – with cultural functions. The development and analysis of a method to test the assumption has raised a variety of complex relationships between sets of other common dualities, like sensible and rational, aesthetics and utility, subjective and objective. While the method did not manage to prove the assumption, its analysis has helped to discuss important issues of working with landscapes, that in their majority represent hybrids of grown and built environment, where their natural and cultural characteristics are in a continuous interplay, complementing each other to create a balanced, sustainable life for everybody.

Literature

Andersson, S. L. (2014). Empowerment of aesthetics. Catalogue for the Danish pavilion at the 14th international architecture exhibition La Biennale Di Venezia 2014.

Brady, E. (2006). The Aesthetics of Agricultural Landscapes and the Relationship between Humans and Nature. Ethics, Place and Environment, 9:1, 1-19, DOI: 10.1080/13668790500518024

Brady E., Phemister, P. (2012). Human-Environment Relations: Transformative Values in Theory and Practice. Springer Science+Business Media B.V. DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-2825-7_7

Dee, C. (1958). To design landscape: art, nature and utility.

Downes, M. & Lange, E. (2014). What you see is not always what you get: A qualitative, comparative analysis of ex ante visualizations with ex post photography of landscape and architectural projects.

Germundsson, T. (2005) Regional cultural heritage versus national heritage in Scania's disputed national landscape. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 11:1, 21-37, DOI: 10.1080/13527250500036791

Hellemondt, I. & Notteboom, B. (2018). Sustaining beauty and beyond. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 13:2, 4-7, DOI: 10.1080/18626033.2018.1553387

Kylin, M. (2003). Children´s dens. Children, Youth and Environments 13 (1)

Lippert M. A. “Cities of nature” (2016). SLA.

Männik, M. L. & Philipson, K. & Linnros F. (2018). Förskolegårdens friyta i förhållande till naturliga material. White Research Lab WRL 2017:26

Reynolds, M. (2016) The garden awakening. Designs to nurture our land and ourselves.

Spirn, A. (1996). Constructing nature: the legacy of Fredrick Law Olmsted.

Steiner, F. (2006) The essential Ian McHarg : writings on design and nature.

Thompson, I. H. (2014). Landscape architecture: Very short introduction. Oxford Press

Unterweger, P. A. & Schrode , N. & Betz, O. (2017). Urban Nature: Perception and Acceptance of Alternative Green Space Management and the Change of Awareness after Provision of Environmental Information. A Chance for Biodiversity Protection. Institut für Evolution und Ökologie, Evolutionsbiologie der Invertebraten, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen.

Wistrand, L. & Michaelsson, S. (2017). Normkreativ visualisering – för mer jämnlika och rättvisa städer. White Arkitekter. Almedalen 4 juli, 2017

Wylie, J. (2005). A single day’s walking: narrating self and landscape on the South West Coast Path

Andersson, S. L. (2014). Empowerment of aesthetics. Catalogue for the Danish pavilion at the 14th international architecture exhibition La Biennale Di Venezia 2014.

Brady, E. (2006). The Aesthetics of Agricultural Landscapes and the Relationship between Humans and Nature. Ethics, Place and Environment, 9:1, 1-19, DOI: 10.1080/13668790500518024

Brady E., Phemister, P. (2012). Human-Environment Relations: Transformative Values in Theory and Practice. Springer Science+Business Media B.V. DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-2825-7_7

Dee, C. (1958). To design landscape: art, nature and utility.

Downes, M. & Lange, E. (2014). What you see is not always what you get: A qualitative, comparative analysis of ex ante visualizations with ex post photography of landscape and architectural projects.

Germundsson, T. (2005) Regional cultural heritage versus national heritage in Scania's disputed national landscape. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 11:1, 21-37, DOI: 10.1080/13527250500036791

Hellemondt, I. & Notteboom, B. (2018). Sustaining beauty and beyond. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 13:2, 4-7, DOI: 10.1080/18626033.2018.1553387

Kylin, M. (2003). Children´s dens. Children, Youth and Environments 13 (1)

Lippert M. A. “Cities of nature” (2016). SLA.

Männik, M. L. & Philipson, K. & Linnros F. (2018). Förskolegårdens friyta i förhållande till naturliga material. White Research Lab WRL 2017:26

Reynolds, M. (2016) The garden awakening. Designs to nurture our land and ourselves.

Spirn, A. (1996). Constructing nature: the legacy of Fredrick Law Olmsted.

Steiner, F. (2006) The essential Ian McHarg : writings on design and nature.

Thompson, I. H. (2014). Landscape architecture: Very short introduction. Oxford Press

Unterweger, P. A. & Schrode , N. & Betz, O. (2017). Urban Nature: Perception and Acceptance of Alternative Green Space Management and the Change of Awareness after Provision of Environmental Information. A Chance for Biodiversity Protection. Institut für Evolution und Ökologie, Evolutionsbiologie der Invertebraten, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen.

Wistrand, L. & Michaelsson, S. (2017). Normkreativ visualisering – för mer jämnlika och rättvisa städer. White Arkitekter. Almedalen 4 juli, 2017

Wylie, J. (2005). A single day’s walking: narrating self and landscape on the South West Coast Path